- Lois et règlements

- eservices

-

Media Center

Hotline for Health Services for Displaced Lebanese 1787Hotline for the Patient Admission to Hospitals 01/832700COVID-19 Vaccine Registration Form covax.moph.gov.lbMoPH Hotline 1214

Are you a new member? Sign up now

- Health Indicators

- text

- Nouvelles Directives pour une Meilleure Mammographie dans les Hôpitaux Gouvernementaux

- Bulletin statistique 2013

- Equipe de travail sur la Sante Mentale et le Support Psychosocial

Let us help you

reach your target.

reach your target.

Key Achievements at a glance

Walid AMMAR MD, Ph.D

Director General of Health

This document lists a selection of 13 Key Achievements of the Ministry of Public Health over the last decade*.

1. The creation of a Unified Beneficiaries Database, its maintenance & updating

In 2003, a unified Beneficiaries Database was created, including beneficiaries of the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), National Social Security Fund (NSSF), Civil Servants Cooperative (CSC), Army, Internal Security Forces (ISF), General Security Forces (GSF) and State Security Forces (SSF). The unification of beneficiaries information implied that double-coverage or double-billing from more than one fund, was no longer possible for beneficiaries, and thus considerably improved the efficiency of the system. It also aimed at simplifying administrative procedures and reducing waiting time for getting the prior authorization of the MOPH for hospital admission.

2. Development of the visa system, its decentralization and linkage to database.

Automation of beneficiaries’ admissions and procedural approval was initiated in 1995. It was however, at the time, limited only to hospitals within Beirut. In 2003, the MOPH began a decentralization process by expanding the system throughout the country through web-linking of all visa centers. By February 2005, the system was completed covering all of Lebanon, and was linked to the Beneficiaries Database.

3. Post-graduate training of inspectors, controllers and other physicians

Two extensive trainings have been held by the MOPH in recent years. The first trainings were on ICD10 classification, took place during 1999-2000, and occurred in two phases: the first targeting MOPH inspectors, who proceeded to the second phase to train both MOPH medical controllers and other physicians at all hospitals nation-wide. A second training was carried out from 2001-2002 at the Université Saint Joseph (USJ), during which MOPH inspectors and medical controllers completed extensive training on coding and controlling admissions and clinical management, with most being awarded University Diploma in this field.

4. Working on payment mechanisms and flat rates.

Prior to 1998, the MOPH payment mechanism was totally based on fee for service and auditing of itemized bills generating clear incentives for over doctoring. The MOPH has first introduced flat-rates for same-day surgeries in March 1998. Subsequently, as a 2nd step flat-rates were also introduced for the most frequent surgical procedures in 2000, and by 2002 all surgical procedures were covered by the MOPH through flat-rate payment. By reversing incentives, this new reimbursement modality had a significant impact on the total hospital bill and contributed to rationalizing the cost of health care.

* W. Ammar; "Health Beyond Politics". WHO, MPH, I S B N 978-9953-515-489, Beirut. January 2009.

5. Setting of a financial ceiling in every contract between hospitals and the MOPH.

In the past, the MOPH contracted with hospitals based on bed capacity. This resulted in yearly overruns of the MOPH budget. However in 2005, the MOPH replaced this by setting fixed annual financial ceilings for each hospital, which allowed for more efficient control of hospital expenditures on the part of the MOPH. As a result, the MOPH did not experience any overruns of its budget set for hospitalization since 2005.

6. Utilization review activities.

Between 2009 and 2014 the MOPH was engaged in the second emergency social protection implementation support project (ESPISP2), funded by a World Bank grant, whose purpose is to increase efficiency of the MOPH’s allocation of funds for contracted public and private hospitals. Much of this activity centered in 3 committees for each of utilization review, clinical guidelines and performance contracting (see below #7) . Achievements included development of 40 clinical guidelines for hospital admission, guideline trainings for MOPH physician controllers, utilization review of numerous high-cost and/or high-volume admissions and investigations of outlier cases. In 2014 the MOPH formalized the utilization review system to identify outlier hospital admissions, and thus flagging suspicious cases for further auditing and/or investigation by the MOPH. This system has developed the MOPH auditing into a more efficient and targeted process.

7. Performance contracting.

In 2014 the MOPH implemented a new contracting system with public and private hospitals, which directly linked hospital performance with the reimbursement rate paid to hospitals for patients under MOPH coverage. This development came following research conducted by the MOPH that indicated that the previous system that relied on linking reimbursement rate solely to hospital accreditation results was not appropriate, and leads to unfairness and inefficiency in the system (Ammar et al. BMC Health Services Research 2013, 13:505). Six factors were chosen as measures of hospital performance: accreditation, patient satisfaction, case-mix index, intensive care unit admissions, proportion of surgical to medical admissions, and deduction rate from the MOPH auditing committee. The main purpose was to set a fair pricing system that reflects the complexity as well as the quality of services provided. Some indicators are integrated to provide incentives and disincentives for hospitals to promote good practice and discourage overuse and abuse of the system. The first two factors, accreditation and patient satisfaction, are a reflection of quality, accounting for 40% and 10% respectively of the total contracting score. The second half of the score is a reflection of performance, with hospital case-mix index accounting for 35%, and 15% shared equally by the remaining factors. Public and private hospitals were contracted based on their results in this new system as of December 2014.

8. Autonomy of public hospitals.

By the end of the civil war, only one third of the country’s, being 24 public hospitals, were operational, with an average of only 20 beds and very low occupancy rates. Following continuous restructuring, rehabilitation and building plans, this had increased to the current 28 public hospitals, with a total of 2550 beds. Through the mid 1990s, the MOPH sought extensively to also establish financial and administrative autonomy for public hospitals, an effort which succeeded by the issuance of a law to this effect in 1996, and was subsequently amended on several occasions. Under this law, administration boards of hospitals are able to sign contracts with financing agencies including the MOPH. Currently all public hospitals have autonomous administration boards appointed by government decrees (Tyr hospital located in a southern Palestinian camp and run by an officer of the Lebanese Army is an exception). Within such a system, the financial risk is shifted from the MOPH central administration down to the level of hospital management, and financial breakeven is essential for survival. Hence, incentives were created for public hospitals to attract patients and reduce transfers. At public hospitals, hospitalized uninsured patients pay 5% of the bill, in comparison with 15% in private hospitals, with the MOPH reimbursing the remainder. With public hospitals costing 10% less to the patient than private hospitals, created incentives for patients to use public hospitals, which have grown to exceed 30% of MOPH admissions in 2008.

9. Contracting with hospitals based on quality and accreditation.

In the past the classification system of hospitals had provided strong financial incentives for hospitals to invest in sophisticated equipment and services without rational planning. The MOPH began the process of introducing accreditation to address this issue in 2000 with the support of an international consultant, with survey of all 128 hospitals in Lebanon being completed by 2002 (47 successful hospitals from 128; 37%), and a follow-up audit in 2002-2003 (39 successful hospitals from 45; 87%). The high success rate in the follow-up indicated to the MOPH that hospitals were becoming committed to accreditation, and the MOPH accreditation system was subsequently updated through upgrading the National Standards and replacing scores by awards, to avoid misuse of the accreditation results by hospitals. A third round of accreditation was held in 2004-2005, and work is ongoing to institute a new accreditation system which falls in line with international standards, using prequalification and selection of non-governmental auditing bodies by independent expert committee, with selected bodies subsequently being authorized by MOPH to officially perform hospital auditing against national standards.

1. The creation of a Unified Beneficiaries Database, its maintenance & updating

In 2003, a unified Beneficiaries Database was created, including beneficiaries of the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), National Social Security Fund (NSSF), Civil Servants Cooperative (CSC), Army, Internal Security Forces (ISF), General Security Forces (GSF) and State Security Forces (SSF). The unification of beneficiaries information implied that double-coverage or double-billing from more than one fund, was no longer possible for beneficiaries, and thus considerably improved the efficiency of the system. It also aimed at simplifying administrative procedures and reducing waiting time for getting the prior authorization of the MOPH for hospital admission.

2. Development of the visa system, its decentralization and linkage to database.

Automation of beneficiaries’ admissions and procedural approval was initiated in 1995. It was however, at the time, limited only to hospitals within Beirut. In 2003, the MOPH began a decentralization process by expanding the system throughout the country through web-linking of all visa centers. By February 2005, the system was completed covering all of Lebanon, and was linked to the Beneficiaries Database.

3. Post-graduate training of inspectors, controllers and other physicians

Two extensive trainings have been held by the MOPH in recent years. The first trainings were on ICD10 classification, took place during 1999-2000, and occurred in two phases: the first targeting MOPH inspectors, who proceeded to the second phase to train both MOPH medical controllers and other physicians at all hospitals nation-wide. A second training was carried out from 2001-2002 at the Université Saint Joseph (USJ), during which MOPH inspectors and medical controllers completed extensive training on coding and controlling admissions and clinical management, with most being awarded University Diploma in this field.

4. Working on payment mechanisms and flat rates.

Prior to 1998, the MOPH payment mechanism was totally based on fee for service and auditing of itemized bills generating clear incentives for over doctoring. The MOPH has first introduced flat-rates for same-day surgeries in March 1998. Subsequently, as a 2nd step flat-rates were also introduced for the most frequent surgical procedures in 2000, and by 2002 all surgical procedures were covered by the MOPH through flat-rate payment. By reversing incentives, this new reimbursement modality had a significant impact on the total hospital bill and contributed to rationalizing the cost of health care.

* W. Ammar; "Health Beyond Politics". WHO, MPH, I S B N 978-9953-515-489, Beirut. January 2009.

5. Setting of a financial ceiling in every contract between hospitals and the MOPH.

In the past, the MOPH contracted with hospitals based on bed capacity. This resulted in yearly overruns of the MOPH budget. However in 2005, the MOPH replaced this by setting fixed annual financial ceilings for each hospital, which allowed for more efficient control of hospital expenditures on the part of the MOPH. As a result, the MOPH did not experience any overruns of its budget set for hospitalization since 2005.

6. Utilization review activities.

Between 2009 and 2014 the MOPH was engaged in the second emergency social protection implementation support project (ESPISP2), funded by a World Bank grant, whose purpose is to increase efficiency of the MOPH’s allocation of funds for contracted public and private hospitals. Much of this activity centered in 3 committees for each of utilization review, clinical guidelines and performance contracting (see below #7) . Achievements included development of 40 clinical guidelines for hospital admission, guideline trainings for MOPH physician controllers, utilization review of numerous high-cost and/or high-volume admissions and investigations of outlier cases. In 2014 the MOPH formalized the utilization review system to identify outlier hospital admissions, and thus flagging suspicious cases for further auditing and/or investigation by the MOPH. This system has developed the MOPH auditing into a more efficient and targeted process.

7. Performance contracting.

In 2014 the MOPH implemented a new contracting system with public and private hospitals, which directly linked hospital performance with the reimbursement rate paid to hospitals for patients under MOPH coverage. This development came following research conducted by the MOPH that indicated that the previous system that relied on linking reimbursement rate solely to hospital accreditation results was not appropriate, and leads to unfairness and inefficiency in the system (Ammar et al. BMC Health Services Research 2013, 13:505). Six factors were chosen as measures of hospital performance: accreditation, patient satisfaction, case-mix index, intensive care unit admissions, proportion of surgical to medical admissions, and deduction rate from the MOPH auditing committee. The main purpose was to set a fair pricing system that reflects the complexity as well as the quality of services provided. Some indicators are integrated to provide incentives and disincentives for hospitals to promote good practice and discourage overuse and abuse of the system. The first two factors, accreditation and patient satisfaction, are a reflection of quality, accounting for 40% and 10% respectively of the total contracting score. The second half of the score is a reflection of performance, with hospital case-mix index accounting for 35%, and 15% shared equally by the remaining factors. Public and private hospitals were contracted based on their results in this new system as of December 2014.

8. Autonomy of public hospitals.

By the end of the civil war, only one third of the country’s, being 24 public hospitals, were operational, with an average of only 20 beds and very low occupancy rates. Following continuous restructuring, rehabilitation and building plans, this had increased to the current 28 public hospitals, with a total of 2550 beds. Through the mid 1990s, the MOPH sought extensively to also establish financial and administrative autonomy for public hospitals, an effort which succeeded by the issuance of a law to this effect in 1996, and was subsequently amended on several occasions. Under this law, administration boards of hospitals are able to sign contracts with financing agencies including the MOPH. Currently all public hospitals have autonomous administration boards appointed by government decrees (Tyr hospital located in a southern Palestinian camp and run by an officer of the Lebanese Army is an exception). Within such a system, the financial risk is shifted from the MOPH central administration down to the level of hospital management, and financial breakeven is essential for survival. Hence, incentives were created for public hospitals to attract patients and reduce transfers. At public hospitals, hospitalized uninsured patients pay 5% of the bill, in comparison with 15% in private hospitals, with the MOPH reimbursing the remainder. With public hospitals costing 10% less to the patient than private hospitals, created incentives for patients to use public hospitals, which have grown to exceed 30% of MOPH admissions in 2008.

9. Contracting with hospitals based on quality and accreditation.

In the past the classification system of hospitals had provided strong financial incentives for hospitals to invest in sophisticated equipment and services without rational planning. The MOPH began the process of introducing accreditation to address this issue in 2000 with the support of an international consultant, with survey of all 128 hospitals in Lebanon being completed by 2002 (47 successful hospitals from 128; 37%), and a follow-up audit in 2002-2003 (39 successful hospitals from 45; 87%). The high success rate in the follow-up indicated to the MOPH that hospitals were becoming committed to accreditation, and the MOPH accreditation system was subsequently updated through upgrading the National Standards and replacing scores by awards, to avoid misuse of the accreditation results by hospitals. A third round of accreditation was held in 2004-2005, and work is ongoing to institute a new accreditation system which falls in line with international standards, using prequalification and selection of non-governmental auditing bodies by independent expert committee, with selected bodies subsequently being authorized by MOPH to officially perform hospital auditing against national standards.

Box 1: Accreditation of Hospitals: A merit system serving efficiency, not only quality

Since May 2000, the quality of hospital care in Lebanon has been witnessing a paradigm shift, from a traditional emphasis on physical structure and equipment, to a broader multidimensional approach that stresses the importance of managerial processes, and clinical outcomes.

The impetus for change came from the MOPH that has developed an external evaluation system for hospitals with the declared aim of promoting continuous quality improvement. This was possible through a new shade of interpretation of an existing law, without the need for a new legislation.

The MOPH sought international expertise to overcome allegations of partiality, and the accreditation was intentionally presented as an activity independent of the Government and other stakeholders to foster elements of probity and transparency.

Accreditation standards were developed following a consensus building process and issued by decrees. Hospitals were audited against these standards in a professional, educative, non-threatening manner, respecting confidentiality, not without initial resistance from hospitals. For, results of the first auditing survey revealed a shocking failure by majority of hospitals in complying to basic standards, only to recover through a high success rate in the follow-up re-audit, showing a better use of resources and a higher degree of commitment to the programme. This allowed for standards upgrading and another round of auditing. The step-wise approach adopted by the Ministry ensured a smooth and gradual hospitals involvement, and led to the creation of cultural shift towards quality practices, although contracting with MOPH was an important incentive for compliance. The MOPH’s undeclared aim was in fact to strengthen its regulation capabilities and to attain better value for money in terms of hospital care financing. As the selection of hospitals to be contracted could then be made on objective quality criteria, freeing the system from any kind of favoritism or discrimination, especially confessional and political ones.

Since May 2000, the quality of hospital care in Lebanon has been witnessing a paradigm shift, from a traditional emphasis on physical structure and equipment, to a broader multidimensional approach that stresses the importance of managerial processes, and clinical outcomes.

The impetus for change came from the MOPH that has developed an external evaluation system for hospitals with the declared aim of promoting continuous quality improvement. This was possible through a new shade of interpretation of an existing law, without the need for a new legislation.

The MOPH sought international expertise to overcome allegations of partiality, and the accreditation was intentionally presented as an activity independent of the Government and other stakeholders to foster elements of probity and transparency.

Accreditation standards were developed following a consensus building process and issued by decrees. Hospitals were audited against these standards in a professional, educative, non-threatening manner, respecting confidentiality, not without initial resistance from hospitals. For, results of the first auditing survey revealed a shocking failure by majority of hospitals in complying to basic standards, only to recover through a high success rate in the follow-up re-audit, showing a better use of resources and a higher degree of commitment to the programme. This allowed for standards upgrading and another round of auditing. The step-wise approach adopted by the Ministry ensured a smooth and gradual hospitals involvement, and led to the creation of cultural shift towards quality practices, although contracting with MOPH was an important incentive for compliance. The MOPH’s undeclared aim was in fact to strengthen its regulation capabilities and to attain better value for money in terms of hospital care financing. As the selection of hospitals to be contracted could then be made on objective quality criteria, freeing the system from any kind of favoritism or discrimination, especially confessional and political ones.

10. Revision of pricing structure of pharmaceutical drugs.

Under the old pricing system created in 1983, the price-dependent profits were in fixed percent for all price brackets of pharmaceutical drugs, which encouraged the importation, dispensing and overpriced expensive drugs. Two ministerial decisions issued by the MOPH in 2005 had considerable impact on the pricing structure. Decision 301/1 adjusted prices based on comparison with neighboring countries (Jordan, KSA), resulting in a price reduction of an average 20% for 872 drugs and estimated savings of USD 24 million per year. Decision 306/1 provided for a new stratified pricing structure that lowered mark-ups set in 1983 and in a degressive manner, and also introduced for the first time a mechanism for periodic price revision. This resulted in price decrease per drug ranging from 3 -15% and estimated savings of USD 27 million per year. The price revision of drugs registered between 2001 and 2006 was achieved targeting 1109 drugs in 2007, and resulting in lowering the public price of 360 drugs with a yearly saving exceeding USD 10 million

11. Strengthening primary healthcare and promoting essential drugs.

The first national conference on Primary Health Care was held in Lebanon in 1991, followed by numerous consultative meetings between the MOPH and relevant stakeholders which led to the development of a National Strategy for Primary Health Care. This initiative subsequently choose among 800 facilities only 29 health centers to form the nucleus of a National Network that grew to include currently about 150 centers with most belonging to NGOs. The MOPH developed contractual agreements with NGOs and recently has included municipalities as third partners in the MOPH-NGOcontract. The MOPH gave considerable support to this effort, with the development of guidelines and health education materials, training activities, developing incentives, purchasing and distribution of vaccines, drugs, medical supplied and equipment. Each health centre has a defined catchments area with an average of 30,000 inhabitants, with only few exceptions. The centers are committed to provide a comprehensive package of services including immunization, essential drugs, cardiology, pediatrics, reproductive health and oral health, and to play an important role in school health, health education, nutrition, environmental health and water control. Provision of essential drugs, vaccines and other services are reported to the MOPH for analysis, evaluation and feedback. Also, centers do not differentiate between insured and uninsured patients regarding nominal fees, with the MOPH policy being to ensure a safety net while providing an alternative to the uninsured to have access to affordable essential services through its network. Such a horizontal approach provided by primary health care complements and cross-cuts with vertical programs in place.

Box 2. Lebanon’s reforms: improving health system efficiency, increasing coverage and lowering out-of-pocket spending

In 1998 Lebanon spent 12.4% of its GDP on health, more than any other country in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Out-of-pocket payments, at 60% of total health spending, were also among the highest in the region, constituting a significant obstacle to low-income people. Since then, a series of reforms has been implemented by the Ministry of Health to improve equity and efficiency.

The key components of this reform have been: a revamping of the public-sector primary-care network; improving quality in public hospitals; and improving the rational use of medical technologies and medicines. The latter has included increasing the use of quality-assured generic medicines. The Ministry of Health has also sought to strengthen its leadership and governance functions through a national regulatory authority for health and biomedical technology, an accreditation system for all hospitals, and contracting with private hospitals for specific inpatient services at specified prices. It now has a database that it uses to monitor service provision in public and private health facilities.

Improved quality of services in the public sector, at both the primary and tertiary levels, has resulted in increased utilization, particularly among the poor. Being a more significant provider of services, the Ministry of Health is now better able to negotiate rates for the services it buys from private hospitals and can use the database to track the unit costs of various hospital services.

Utilization of preventive, promotive and curative services, particularly among the poor, has improved since 1998, as have health outcomes. Reduced spending on medicines, combined with other efficiency gains, means that health spending as a share of GDP has fallen from 12.4% to 8.4%. Out-of-pocket spending as a share of total health spending fell from 60% to 44%, increasing the levels of financial risk protection. (Health Reform in Lebanon: A success story in the"WHO Report 2010 on Health Care Financing")

In 1998 Lebanon spent 12.4% of its GDP on health, more than any other country in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Out-of-pocket payments, at 60% of total health spending, were also among the highest in the region, constituting a significant obstacle to low-income people. Since then, a series of reforms has been implemented by the Ministry of Health to improve equity and efficiency.

The key components of this reform have been: a revamping of the public-sector primary-care network; improving quality in public hospitals; and improving the rational use of medical technologies and medicines. The latter has included increasing the use of quality-assured generic medicines. The Ministry of Health has also sought to strengthen its leadership and governance functions through a national regulatory authority for health and biomedical technology, an accreditation system for all hospitals, and contracting with private hospitals for specific inpatient services at specified prices. It now has a database that it uses to monitor service provision in public and private health facilities.

Improved quality of services in the public sector, at both the primary and tertiary levels, has resulted in increased utilization, particularly among the poor. Being a more significant provider of services, the Ministry of Health is now better able to negotiate rates for the services it buys from private hospitals and can use the database to track the unit costs of various hospital services.

Utilization of preventive, promotive and curative services, particularly among the poor, has improved since 1998, as have health outcomes. Reduced spending on medicines, combined with other efficiency gains, means that health spending as a share of GDP has fallen from 12.4% to 8.4%. Out-of-pocket spending as a share of total health spending fell from 60% to 44%, increasing the levels of financial risk protection. (Health Reform in Lebanon: A success story in the"WHO Report 2010 on Health Care Financing")

12. The Epidemiological Surveillance Program (ESU)

Created in 1995, the ESU is responsible of the surveillance system of communicable diseases and national cancer registry. The ESU operates the national surveillance system for communicable diseases, screens epidemiological alerts, conducts field investigations and analytic epidemiological studies, provides feedback to health professionals, and trains them on surveillance tools.

The national epidemiological information system consists of several components:

- Universal reporting system on communicable diseases for 37 target diseases and syndromes (Law of 1957)

- Hospital-based weekly zero reporting for immediately notifiable diseases (150 hospitals)

- Hospital active surveillance for high priority diseases

- Dispensary-based weekly/monthly zero reporting

- Ambulatory sentinel surveillance for private clinics

- Hospital causes of deaths surveillance

- Laboratory-based surveillance for salmonella with molecular subtyping

- School absenteeism monitoring

- Rabies exposure statistics reported from anti-rabies centers

- Snake bites surveillance reported from hospital Emergency Units

- Mass gathering surveillance (Francophony games Beirut 2009, Arabic School Games Lebanon 2010)…

Disease control includes Acute Flaccid Paralysis surveillance for poliovirus eradication as well as rash and fever surveillance for measles elimination. Other entities under control are: food poisoning, meningitis, neonatal tetanus, rabies typhoid fever, viral hepatitis A, dysentery, brucellosis and others.

The Epidemiological Surveillance Unit publishes its reports and figures on the MOPH website with weekly updates on the following website.

http//www.moph.gov.lb (prevention, surveillance)

or http://www.moph.gov.lb/Prevention/Surveillance/Pages/Surveillance.aspx

13. Supply of human resources: Government intervention versus market forces

Regulation of the supply of human resources could not have a significant impact unless it targets the admission of entrants to universities and technical schools. The most common approach, that proved to be effective in selecting a limited number of students, is the numerous clausus. Restrictive measures of this kind could not be implemented in Lebanon for two main reasons. First, because it is considered culturally and politically as an unacceptable interference with personal freedom of career choice. Second, because an important number of Lebanese health professionals are yearly graduating from foreign universities, and can hardly be subjected to national control mechanisms. Lebanese Diaspora, that counts more than the number of residence, is particularly out of reach in this regard.

In the absence of an up stream control, down stream measures such as licensing requirements and the colloquium exam have meaningless effect on the supply volume of concerned professionals.

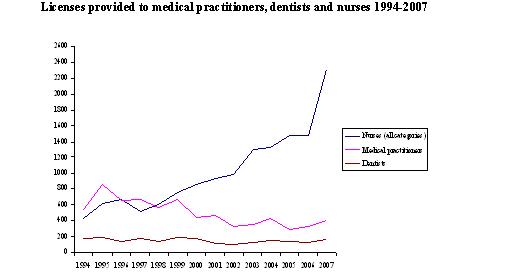

Incapable of playing a meaningful role in reducing oversupply, the MOPH was only able to focus on addressing shortages, particularly that of nurses. MOPH interventions in financing university education programs, in conducting training, in creating and supporting the Nurses’ Order and in improving their financial and work conditions, had a remarkable impact on promoting the nursing profession. The figure below illustrates how in a liberal health system, where government control is ineffective, oversupply can only be partially adjusted by market mechanisms (the slightly declining medical practitioners curve), whereas the regulation authority may intervene and have a significant impact on undersupply by filling specific gaps (the mounting curve of nurses production).

The Epidemiological Surveillance Unit publishes its reports and figures on the MOPH website with weekly updates on the following website.

http//www.moph.gov.lb (prevention, surveillance)

or http://www.moph.gov.lb/Prevention/Surveillance/Pages/Surveillance.aspx

13. Supply of human resources: Government intervention versus market forces

Regulation of the supply of human resources could not have a significant impact unless it targets the admission of entrants to universities and technical schools. The most common approach, that proved to be effective in selecting a limited number of students, is the numerous clausus. Restrictive measures of this kind could not be implemented in Lebanon for two main reasons. First, because it is considered culturally and politically as an unacceptable interference with personal freedom of career choice. Second, because an important number of Lebanese health professionals are yearly graduating from foreign universities, and can hardly be subjected to national control mechanisms. Lebanese Diaspora, that counts more than the number of residence, is particularly out of reach in this regard.

In the absence of an up stream control, down stream measures such as licensing requirements and the colloquium exam have meaningless effect on the supply volume of concerned professionals.

Incapable of playing a meaningful role in reducing oversupply, the MOPH was only able to focus on addressing shortages, particularly that of nurses. MOPH interventions in financing university education programs, in conducting training, in creating and supporting the Nurses’ Order and in improving their financial and work conditions, had a remarkable impact on promoting the nursing profession. The figure below illustrates how in a liberal health system, where government control is ineffective, oversupply can only be partially adjusted by market mechanisms (the slightly declining medical practitioners curve), whereas the regulation authority may intervene and have a significant impact on undersupply by filling specific gaps (the mounting curve of nurses production).